Irrigation Farming: Advantages and Case Study of Sudan's Gezira Scheme

Irrigation Farming

Definition

Irrigation farming is an agricultural practice involving the artificial provision of water for plant growth, either permanently or temporarily. It is carried out under the following conditions:

- Where natural precipitation is insufficient to meet plant moisture requirements.

- Where rainfall is adequate but its seasonal pattern is not suitable for proper crop cultivation.

- Where flooding is common and irrigation helps to utilize flood-prone areas for agriculture.

Types of Irrigation

1. Lifting Devices

Water may be lifted from a well, river, or canal using buckets or mechanical tools. Traditional devices such as the shadoof, Archimedean screw, water wheel, and treadmill have been used for thousands of years. In modern times, diesel, steam, or electrically operated pumps are employed, especially where water is sourced from deep wells.

2. Basin Irrigation

This method has been practiced in Egypt for centuries, though it's less important today. During the Nile’s summer rise, floodwater is channeled into basin-shaped fields through controlled sluices. Basin irrigation using canal water is also used to grow paddy in the United States.

3. Tanks

Tanks are small reservoirs used to store rainwater. Common in southern India and Sri Lanka, these tanks help extend the growing season, although they rarely provide year-round water supply.

4. Canal Irrigation

Canals divert irrigation water from rivers or storage lakes. There are two types:

- Inundation Canals: Operate during flood seasons and do not offer a consistent year-round water supply.

- Perennial Canals: Supplied by water stored behind large dams or barrages and provide irrigation year-round. These systems can direct water to canals both below and above the dam by raising the river’s water level.

5. Overhead Irrigation

This modern technique involves sprays and sprinklers set up in fields and connected via hoses to public water supplies. Though the initial cost is high and requires constant pumping, it is widely used in countries like the USA, Britain, and Europe.

Advantages of Irrigation Farming

1. Increased Cultivable Land

Irrigation allows farming in areas like deserts, where cultivation would otherwise be impossible.

2. Year-Round Cultivation

Crops can be grown throughout the year, not just in the rainy season, leading to higher yields.

3. Enhanced Soil Fertility

Irrigation water, especially from flood rivers, often carries silt which enriches the soil.

4. Salinity Reduction in Deserts

Continuous water flow through the soil in desert regions helps reduce soil salinity.

Additional Advantages of Irrigation Farming

Modern irrigation farming offers a wide range of benefits that extend beyond just crop production. One major advantage is;

Flood control, as modern multi-purpose dams not only provide a reliable water supply but also help mitigate the devastating effects of seasonal flooding, protecting both human lives and agricultural investments. For example, the construction of large dams like the Aswan High Dam in Egypt or the Sennar Dam in Sudan has significantly reduced flood-related disasters.

Additionally, irrigation greatly contributes to increased farmer incomes. With a reliable water source, farmers can achieve higher crop yields and harvests, leading to better returns and improved standards of living.

This success in agriculture also stimulates a boost in foreign exchange earnings, as surplus crops—particularly cash crops like cotton, rice, and sugarcane—are exported to global markets. Countries like India, Sudan, and Vietnam have benefitted significantly from exporting irrigated crops.

Moreover, irrigation enables double cropping, allowing farmers in countries such as Malaysia, China, and India to grow two or even three crops per year instead of relying on a single rain-fed season. This intensification improves food production and supports food self-sufficiency.

A notable example is China, which has achieved near-complete food self-reliance in staple crops like rice and wheat through well-managed irrigation systems. In parallel, job creation is another key benefit of irrigation farming. The construction and maintenance of canals, reservoirs, pumping stations, and distribution systems provide employment to engineers, technicians, laborers, and other professionals.

Lastly, irrigation enhances natural soil fertility—particularly in water-logged fields where algae thrive. These algae biologically fix atmospheric nitrogen, enriching the soil with essential nutrients and contributing to the long-term sustainability of agriculture.

Case Study: Irrigation Farming in Sudan – The Gezira Scheme.

Overview

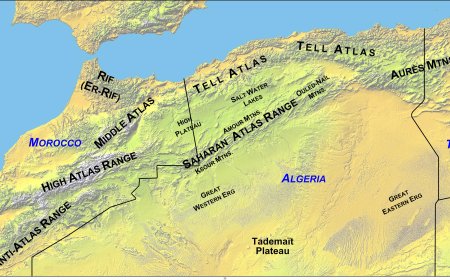

Nowhere in Africa have the benefits of irrigation farming been more evident than along the Nile River in Sudan. One of the most notable irrigation projects in the region is the Gezira Irrigation Scheme, including its Western Managil Extension. This project occupies the triangular area between the Blue Nile and White Nile rivers.

The climatic conditions in central Sudan, particularly in the regions served by the Gezira Irrigation Scheme, were initially a major barrier to sustainable agriculture. Rainfall in the area is both low and unreliable—Sennar receives only about 460 mm of rain per year, while Khartoum gets even less at approximately 160 mm annually. Prior to the development of irrigation infrastructure, communities in the region faced numerous challenges. Seasonal flooding caused by fluctuating water levels in the Blue and White Nile rivers often damaged crops and settlements. At the same time, the scarcity of rain meant that arable land was extremely limited, making it difficult to cultivate crops consistently. These conditions led to frequent famines, especially during prolonged droughts or failed harvests. Most residents depended on subsistence farming, primarily growing millet, and practiced semi-pastoralism, raising livestock in areas that could support them seasonally.

In response to these challenges, the Gezira Irrigation Scheme was conceived as a transformative solution. Originally proposed in 1904, the scheme took a significant step forward with the construction of the Sennar Dam, which began in 1913 and was completed in 1925. This dam functions as both a water reservoir and a regulator of water levels within the expansive network of irrigation canals. The physical geography of the region, with its flat and gently sloping plains, made it ideal for the development of a gravity-fed canal system. Water from the Blue Nile is channeled through a main canal, which then distributes it into branch canals that reach individual farm plots, ensuring a controlled and consistent water supply throughout the year.

Thanks to irrigation, a wide variety of crops can now be grown in the region. Cotton remains the primary cash crop, and it has been instrumental in boosting Sudan's export revenues. In addition, farmers cultivate groundnuts, maize, dura, lubia (a versatile food and fodder bean), millet, and sorghum, all of which contribute to both local food security and economic development. The Gezira Scheme has thus transformed what was once a drought-prone and famine-stricken region into one of the most productive agricultural zones in Sudan.

Other Major Irrigation Schemes in Sudan

In addition to the Gezira Scheme, Sudan is home to several other significant irrigation projects:

- Kenana Sugar Scheme

Located along the White Nile, this scheme primarily supports sugarcane production. - Rahad Scheme

Found along the River Rahad, it produces cotton and groundnuts as cash crops, while dura, maize, and vegetables are cultivated for food. - Gash Delta Scheme

Situated near the town of Kasala, east of Khartoum, it uses water from the Gash River. - Khashm el Girba Scheme

This scheme sources its water from the Atbara River. The main crops grown include wheat, groundnuts, cotton, and sugarcane. - Tokar Delta Scheme

Located on the Red Sea coast, south of Suakin, this area focuses mainly on cotton production.

In addition to these, there are numerous government and privately-owned irrigation schemes, especially concentrated along the Blue and White Niles.

Factors Favoring Large Irrigation Schemes in Sudan

Several interrelated physical, environmental, and socio-economic factors have favoured the establishment of large-scale irrigation schemes in Sudan.

Arid climate, with much of the land receiving less than 500 mm of rainfall annually, makes rain-fed agriculture highly unreliable. Irrigation has thus become essential for any meaningful crop cultivation. Fortunately, Sudan is rich in perennial rivers, including the Blue Nile, White Nile, Gash, Baraka, Atbara, and Rahad rivers, which offer a consistent and sustainable water supply crucial for large irrigation projects. These rivers support major schemes like the Gezira, Rahad, and Kenana plantations.

The soil characteristics in many regions further support irrigation farming. For example, the area between the Blue and White Nile benefits from fertile alluvial soils deposited during seasonal floods. These soils are ideal for cultivating both food and cash crops. In addition, the high clay content in these soils helps retain water and creates a natural seal in irrigation canals, eliminating the need for costly artificial lining. Large tracts of available land, such as the sparsely populated Gezira region, allowed for the development of vast irrigation fields without major displacement, while favourable topography, including a flat landscape and gentle northern slope, has made canal construction both easy and cost-effective. In the Gezira Scheme, for instance, gravity-fed irrigation works efficiently with minimal need for pumping.

Sudan's climatic conditions also complement irrigation farming. With a stable water supply, the climate becomes ideal for cotton cultivation, the country’s key cash crop. Moreover, the arid environment reduces the presence of pests and diseases, such as the destructive boll weevil, which would otherwise threaten crops. Because most of Sudan lies above the water table, there is minimal risk of waterlogging, a common problem in many other irrigation regions.

Beyond physical and environmental conditions, demographic and economic factors have also encouraged irrigation development. As Sudan’s population continues to grow, there has been a pressing need to increase food production to feed the nation. At the same time, Sudan has a long tradition of irrigation, dating back to the use of simple shadoofs and floodwater farming, giving local communities valuable experience to build upon. The drive to diversify agriculture beyond cereals to include cotton, sugarcane, vegetables, and dairy products also played a key role. These crops not only provide food but also serve as raw materials for local industries, such as cotton for textiles and sugarcane for sugar processing.

Furthermore, Sudan enjoys access to both local and international markets, particularly for cotton, which is exported to countries like the United Kingdom, Japan, Italy, Germany, and India. Finally, the availability of capital investment, provided by the Sudanese government and friendly nations like Britain and Arab states, enabled the construction of critical infrastructure such as the Sennar and Roseires dams, irrigation canals, and the acquisition of farm machinery. All these factors combined to make Sudan one of the leading irrigation-based agricultural nations in Africa.

Benefits of Irrigation Farming in Sudan (with Illustrations)

Irrigation farming in Sudan has led to numerous social and economic benefits, transforming the country’s agricultural sector. One of the most direct benefits is the creation of employment opportunities for the local population. For instance, during the construction of massive projects like the Sennar Dam and the digging of irrigation canals in the Gezira Scheme, thousands of Sudanese workers were employed. Even today, locals work as farm labourers, canal maintenance workers, technicians, and administrators in these schemes.

Another major benefit is the expansion of cultivated land. Before irrigation, vast areas such as the Gezira region were underutilized due to erratic rainfall. With the introduction of irrigation, over 850,000 hectares of land in the Gezira and Managil extensions are now cultivated. Similarly, irrigation has made it possible to farm 120,000 hectares in Rahad, 30,000 in Kenana, and 200,000 in Damazin — areas that were previously too dry for serious farming.

Food production has also increased significantly. Crops like dura (sorghum), millet, wheat, groundnuts, vegetables, and lubia are now grown in large quantities. For example, in Rahad, vegetables and food grains grown through irrigation are supplied to urban markets in Khartoum and Port Sudan, reducing the need for food imports. This not only enhances food security but also saves valuable foreign exchange that would have been used to buy food from abroad.

The schemes have also facilitated the introduction of cash crops. Cotton stands out as the most prominent cash crop, especially in the Gezira Scheme, where thousands of hectares are dedicated to its cultivation. Sugarcane production in the Kenana Scheme and the cultivation of cotton and groundnuts in the Rahad Scheme are other examples. These crops are not only sold locally but also exported, contributing to national revenue.

Foreign exchange earnings have increased due to the export of these cash crops. Sudan's cotton, grown primarily in the Gezira, is exported to countries such as Germany, Japan, China, and India. Cotton alone accounts for nearly 50% of Sudan’s foreign exchange earnings, making it a cornerstone of the country's economy.

This growth in agricultural activity has raised farmers’ incomes. For example, farmers in the Gezira Scheme, referred to as "tenants," receive a share of the profits from cotton sales. These earnings have enabled them to buy items such as radios, sewing machines, bicycles, and in some cases, even cars. This reflects a rising standard of living and improved household welfare.

With the support of irrigation, farmers have also adopted modern agricultural techniques. Improved seed varieties, chemical fertilizers, and the use of tractors are now more common. The practice of crop rotation, such as alternating between cotton, sorghum, millet, and beans, has been adopted to maintain soil fertility. For instance, alternating cotton with leguminous crops helps fix nitrogen in the soil, reducing the need for artificial fertilizers.

Moreover, industrial development has been stimulated by irrigation schemes. The steady supply of cotton has encouraged the growth of ginneries in Hassa Heisa, Managil, and Barakat, and textile industries in Khartoum and Wad Medani. Other related industries, such as those manufacturing farm machinery, processing sugar, producing dairy products, and making fertilizers, have also developed. These industries create more jobs and add value to raw materials produced by the farmers.

In addition to the many benefits already discussed, irrigation farming in Sudan has led to a significant increase in the number of tenant farmers, particularly in the Gezira Scheme and its Managil extension, which now hosts over 85,000 tenants. The concentration of people in one area has made it easier for the government to provide essential social services such as clean water, health centres, schools, agricultural training facilities, and leisure centres. Infrastructure development has also been spurred by irrigation, with roads and light railways built to transport cotton and other produce to central collection points and onward to Port Sudan for export via rail from Khartoum.

The success of the Gezira Scheme has made it a model for other irrigation projects in the country. For instance, the Rahad Project, Damazin Irrigation Scheme, and the Kenana Sugar Plantation were all designed using lessons learned from Gezira. These newer schemes benefit from improved planning and better management, avoiding many of the earlier mistakes. Irrigation has also been a major source of employment, both directly and indirectly. Tens of thousands of people are employed as casual labourers, field inspectors, tractor drivers, mechanics, managers, and farm advisors. Every year, over a million landless labourers and their families are hired during the cotton and food crop harvest seasons.

The construction of dams like the Sennar Dam has helped control flooding, particularly along the Nile, which previously caused seasonal damage to farms. Furthermore, the schemes are not limited to agriculture alone. Forests, especially eucalyptus, have been planted to supply fuel and construction materials, while dairy farming has emerged using crops like lubia as fodder. This shows the diversification made possible by reliable irrigation.

Irrigation schemes have also become tourist attractions, with international visitors coming to view large-scale farming projects and dams, contributing to foreign exchange earnings. The dependency on unpredictable natural weather has also been reduced. In areas like the Gezira, rain failure no longer results in famine, since water for crops can now be supplied all year round. These schemes have also spurred the growth of urban centres such as Kosti, Hassa Heisa, Wad Medani, Barakat, and Managil, where produce is processed and traded, creating hubs of economic activity.

The schemes contribute significantly to government revenue through taxes collected from tenant farmers and agro-industries. Sudan has also used its irrigation development to foster international cooperation, working with countries that import its crops — such as China, Japan, and Saudi Arabia — and partnering with nations that have supported dam construction, including the United Kingdom and Arab countries.

However, despite these benefits, irrigation farming in Sudan also has its shortcomings. One of the main challenges is the spread of diseases like bilharzia. The snails that carry the disease thrive in slow-moving irrigation canals, unlike in the fast-flowing Blue Nile where they cannot survive. The canals of the Gezira Scheme, for example, have become breeding grounds for these snails, putting human health at risk.

Challenges Facing Irrigation Farming in Sudan

Despite the many successes achieved through irrigation farming in Sudan, several significant challenges continue to limit its full potential and threaten its long-term sustainability.

One major issue is market-related: the schemes produce commodities such as cotton, wheat, and sugarcane, which are subject to unpredictable price fluctuations on the international market. For example, when the global price of cotton drops, both farmers in the Gezira Scheme and the government suffer losses in income and revenue, making economic planning difficult.

Management and efficiency problems also persist, especially in large-scale schemes like Gezira. The sheer size of such projects makes it hard for individual farmers to manage their plots effectively. Additionally, administrative and maintenance costs are high, requiring significant investment from the government and cooperative unions. These costs can strain national resources, particularly in times of economic difficulty.

Environmental and soil-related challenges further complicate irrigation farming. One of the persistent problems is siltation, where irrigation canals and artificial reservoirs become clogged with sediments carried by irrigation water. For example, in the Gezira scheme, regular and expensive dredging is required to keep the canals functional. Moreover, high evaporation rates, a result of Sudan's hot and dry climate, lead to the accumulation of salts in the soil. This salinity reduces agricultural productivity over time. The repeated planting of the same crops, especially cotton in Gezira and sugarcane in Kenana, has led to soil exhaustion, depleting the land of essential nutrients and making it less fertile.

The social and ecological consequences of irrigation schemes also cannot be ignored. In many cases, large-scale projects have displaced local communities, forcing the government to create costly and often insufficient resettlement programs. Pollution is another major concern, as the widespread use of fertilizers and agrochemicals contaminates both the Blue and White Nile, as well as nearby farmlands, affecting aquatic life and soil quality. Moreover, invasive waterweeds, such as the rhizome-like Seid, flourish in Sudan’s hot climate. These weeds not only compete with crops for nutrients but also choke irrigation canals, disrupting water flow and making canal maintenance more difficult and expensive.

Summary Notes

What is Irrigation Farming?

Irrigation farming is the artificial supply of water to land to help grow crops, especially in dry areas or during dry seasons.

Common Irrigation Methods

- Lifting Devices – e.g. shadoofs, pumps (lift water from wells/rivers)

- Basin Irrigation – stores floodwater in basins (e.g. ancient Egypt)

- Tanks – store rainwater in reservoirs (common in India/Sri Lanka)

- Canals – draw water from rivers via man-made channels

- Sprinklers (Overhead Irrigation) – modern method like rain from pipes

Benefits of Irrigation Farming

- Turns deserts into farms – makes dry lands productive

- Farming all year – not limited by rainy seasons

- Increases food and income – more crops = more food + earnings

- Controls floods – dams help manage excess river water

- Reduces soil saltiness – washes away salts that damage crops

- Boosts exports – cash crops like cotton bring in foreign exchange

- Allows double cropping – grow 2+ crops per year

- Creates jobs – from farming to irrigation maintenance

- Improves soil fertility – through silt and algae growth

Case Study: Gezira Irrigation Scheme – Sudan

Location

- Lies between the Blue Nile and White Nile rivers

- Covers over 2 million hectares (one of the largest in Africa)

History

- Started in 1904, expanded after building the Sennar Dam in 1925

- Built to grow cotton for British textile industries

Crops Grown

- Main Crop: Cotton (exported)

- Other Crops: Groundnuts, maize, millet, sorghum (for local use)

Achievements

- Major export earner for Sudan

- Improved food supply in the region

- Created jobs and towns (e.g. Wad Medani)

- Boosted farming income and introduced modern agriculture

- Provided education, roads, health services to rural areas

Challenges Faced

- Health Risks – stagnant water spreads diseases like bilharzia

- Dependence on Cotton – risky if cotton prices fall

- Soil Salinity – poor drainage increases salt in soil

- Canal Maintenance – blocked by silt and weeds

- Management Issues – difficult to organize thousands of farmers

Conclusion

- Irrigation farming is crucial for food security and economic growth, especially in dry regions.

- The Gezira Scheme proves that large-scale irrigation can transform deserts into productive farmland, but it also requires sustainable management and continuous improvement.