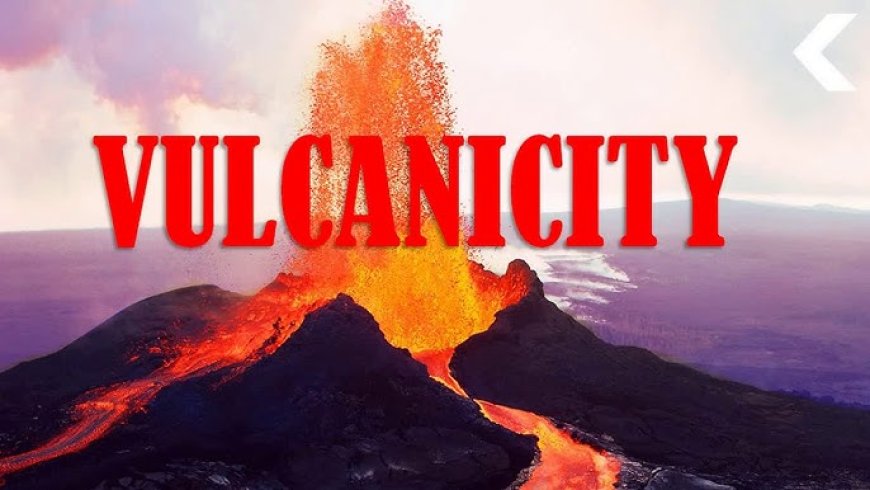

Understanding Vulcanicity in East Africa: Formation, Effects, and Examples

Discover the role of vulcanicity in East Africa, from how volcanoes form to their effects on landscapes, climate, and human life. Explore key examples like Mount Kilimanjaro and the Great Rift Valley.

What is Vulcanicity?

The term vulcanicity includes in its widest sense all processes by which solid, liquid and gaseous materials collectively known as magma are intruded into the earth's crust or extruded onto the earth's surface. Vulcanicity is also referred to as igneous activity.

Vulcanism originates from upper layers of the mantle and to a less extent the base of the earth's crust. Magma is molten or partially molten rock in the upper (outer) mantle and less commonly in the base of the earth's crust. Very hot temperatures and high pressure are needed for the formation of magma. The temperature in this part is over 3,700°C and it is where most of the internal heat of the earth is located. The heat is generated in a number of ways; radio-activity, geo-chemical reactions and friction along rock surfaces at the boundaries of the tectonic plates by faulting and other earth movements. The heat is accompanied with very high pressure partly generated by the height of the overlying masses of the crust onto the mantle. The end result is having great heat and pressure within the interior of the earth.

Once the magma bas formed, convectional currents begin to form within the mantle in which magma rises vertically and laterally before sinking back into the interior. These movements as well as friction along rock surfaces at the boundaries of the tectonic plates create lines of weakness known as faults or fissures. The magma rises through these fissures due to the convectional currents set up within the mantle and because it is less dense than the solid rock surrounding it.

Vulcanicity Taking place.

As the individual magma droplets rise, they join to form ever-larger blobs and move toward the surface. The larger the rising blob or lumps of magma, the easier it moves. Rising magma does not reach the surface in a steady manner but tends to accumulate in one or more underground storage regions, called magma reservoirs, before it erupts onto the surface. When magma comes to the surface, it is red-hot, reaching temperatures as high as 1,200° C. At the surface it cools and solidifies to form various extrusive volcanic landforms. It is important to note that when magma erupts at the surface of the earth and loses its gases, it is known as lava. On the other hand as the magma moves upwards, it encounters colder rock and begins to cool. If the temperature of the magma drops low enough, the magma will crystallize underground to form rock and various intrusive volcanic landforms.

The magma can erupt through one fissure (vent) or a cluster of fissures. The eruptions may be explosive or non-explosive depending on the quantity of gases. Acidic lava tends to contain most gas and basaltic lava tends to contain the least. Explosive eruptions can eject liquid and

semi-solid lava as well as solid fragments of volcanic or non-volcanic rock that have been carried along by the rising magma before eruption. Very violent eruptions often contain a lot of gases and can last for several hours to days. The materials consist of acid lava with is thick and can be eject long distances from the vents. Non-violent eruptions are associated with basalt lava flows and presence of few gases. The lava comes out of the vent and flows quietlyto the surrounding country side.

Volcanic materials

Extrusive and intrusive volcanic features are formed when material escape through a vent, fault or opening onto the earth surface or below the earth's surface. The resultant landforms largely depend on the nature of materials ejected. The materials ejected include;

1.Gaseous materials

All eruptions, explosive or non-explosive, are accompanied by the release of volcanic gas. The sudden escape of high-pressure volcanic gas from magma is the driving force for eruptions. Gases come from the magma itself or from the hot magma coming into contact with water in the ground. Volcanic gases appear dark during an eruption because these gases are mixed with dark- colored materials such as tephra. Most volcanic gases predominantly consist of water vapor (steam), with carbon dioxide (CO2) and sulfur dioxide (SO2) being the next two most common compounds along with smaller amounts of chlorine and fluorine gases.

2.Solids

When an eruption takes place, various materials are ejected. These include the following:

Basic lava

This is lava with a silica content of less than 50 percent by weight. The lava tends to be thin, fluid and mobile. It can flow long distances before solidifying.

Acid lava or rhyolitic

This is lava in which silica (silicon dioxide) makes up more than 65 percent of the weight of the lava. Such lava is thick and viscous and can flow only short distances before solidifying.The oozes slowly from the earth's crust like toothpaste.

Intermediate lava or andesitic

This is lava with silica content between 50 percent and 65 percent by weight. Andesitic lava is intermediate in composition between basaltic and rhyolitic lava. It is fairly viscous.

Tephra

The term tephra or pyroclastic is of Greek origin and means "fire-broken". It is a general term for fragments of volcanic rock and lava that are blasted into the air by explosions or carried upward by hot gases in eruption columns or lava fountains. It includes large, dense blocks and bombs and small, light rock debris such as scoria, pumice and ash.

Volcanic ash and dust.

Pyroclasts are further subdivided depending on their size, shape, texture, and composition. For example, very small fragments, less than a thousandth of a millimetre in diameter, are called volcanic dust and have the texture of flour. Other fragments, called volcanic ash, are a little larger and grittier than dust but are less than 2 mm in diameter.

3. Liquids

This is usually the most important product of an eruption when magma reaches the earth surface. The material cools and solidifies at the surface. The nature of volcanic material formed largely depends on the degree of silica present in that material.

Global distribution of vulcanicity.

Scientists have determined that there is a close connection between the formation of volcanoes, and the movement of the tectonic plates. Nearly 80% of the earth's volcanoes are found near the tectonic plate boundaries of the Pacific Ocean. The oceanic crust is subducting, or plunging beneath, the continental crust in this region. Volcanoes can also be found at divergent plate boundaries where tectonic plates are splitting apart, or in the middle of tectonic plates, such as the volcanoes of the Hawaiian Islands in the North Pacific Ocean. However, some volcanoes are located thousands of kilometers from any active plate boundary. We can therefore conclude that vulcanicity is largely associated with areas of crustal instability such as crustal movements and faulting.

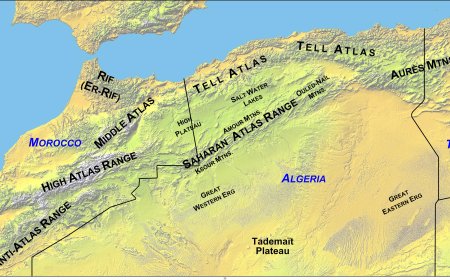

VULCANISM IN EAST AFRICA

Vulcanism has contributed significantly to the shaping of the East African landscape throughout geological time. However, the most important period of large-scale volcanism was from Tertiary up to the recent periods. Volcanoes such as Mt. Elgon, Mt. Napak and Mt. Kadam are thought to have erupted about 25 million years ago. The most spectacular products of volcanism are several major peaks associated with the Great Rift Valley system in East Africa. These now dormant peaks include Kilimanjaro, Mount Kenya and Mount Meru. The Ol Doinyo Lenga in northern Tanzania, and the Nyiragongo and Nyamulagira in the Virunga Mountains along the border between Rwanda and the DRC are active volcanoes.

Intrusive volcanicity.

When, magma is injected into the earth's crust and solidifies before reacting the earth's surface, intrusive forms of volcanicity occur. The landforms resulting from intrusive volcanicity depend on two main factors;

The degree of fluidity of the magma. Basic magma is very fluid and therefore able to flow over long distances before solidifying while acid magma is viscous, cohesive and sticky and therefore unable to spread over long distances before solidifying. Landforms resulting from intrusive volcanicity lie below the earth’s surface but may later be exposed to the surface by denudational processes. The term denudation refers to all processes which wear down the earth's surface such as erosion, weathering and mass movement.

The major intrusive volcanic landforms in East Africa are shown in Fig 6.001 above. Note however that landforms do not occur together as shown in the diagram but for purposes of simplicity they have been shown as such.

Intrusive volcanic landforms

Dykes

Dykes are vertical or steeply inclined rock sheets intruded into fissures or cracks. They are formed when magma rises through a vertical fissure or fault either vertically or inclined but solidifies before reaching the earth's surface to form wall-like features. They cut discordantly across the sedimentary rock strata. Their thickness varies from a few centimeters to hundreds of meters. The thick and viscous magma forms resistant dykes for example. those forming the Doinyo Sapuk as well as the and Isingiro ridges on the Ankole -Buganda border. On the other hand, the fluid and mobile magma forms weak dykes which can easily be eroded e.g. those forming the linear trenches west of Lake Turkana in Kenya. Dykes may occur either singly or in large swarms. The Tororo Rock for example is surrounded by a ring of complex dykes, as well as the dykes in Kaksingri, south Nyanza and Thika district of Kenya.

Photo of a Dyke

Sills

Sills are tabular or horizontal sheets of igneous rocks intruded horizontally into fissures or cracks of sedimentary rocks. Sills form from basic magma which is very fluid and mobile and therefore able to flow long distances before solidifying. They form when this lava intrudes bedding planes of rocks horizontally before solidifying under the earth's crust. Their thickness varies from a few centimeters to hundreds of meters. They are concordant with rock strata. They may occur singly or in large groups. They form flat topped hills when exposed to the surface by denudation. Where sills have been crossed by rivers, waterfalls are the result e.g. Sezibwa falls on River Sezibwa, as well as Karuma falls and Bujagali falls on the Nile River. Others occur in the Thika district of Kenya.

Lopolith

This is a very large saucer-shaped igneous intrusion within the county rocks. It is formed when large quantity of acid magma which is thick and sticky gets intruded through vents into the bedding planes of the country rocks in the interior of the earth's crust. The shape is due to increased weight from the overlying rocks causing the rocks to sink e.g. at Ambereny massifs in Madagascar. When exposed to the surface by denudation, shallow depressions are formed e.g. Rubanda arena along the Kabale Kiroro road.

Laccoliths

These are dome-shaped landforms with a flat bottom or floor. They are formed from viscous magma, which is adhesive and sticky. It rises from the interior of the earth but it is unable to flow over long distances and instead of spreading widely, it heaps up at a particular level arching up the overlying rocks. When exposed to the surface by denudation, laccoliths form dome-shaped hills or inselbergs e.g. at Labwor in Kotido, Kalongo in Pader, Parabong in Kitgum, Lion rocks in Kitui and Bunyanga hill in Bunyore (Kenya).

Batholith

This is the largest intrusive voice landform. It consists of a very large dome shaped intrusion of magma. It is formed by the intrusion of a very large mass of magma usually of granite rock that solidifies at great depth covering hundreds of square kilometers. Batholiths occur below the earth's surface but some have been exposed at the surface by denudation. Mubende batholith, Tanganyika batholiths, Bismack Rock at Mwanz, Kachumbala batholiths in Kani, and several other localities such as iringa, Moyale and El Wak.

Effects of intrusive voicanicity on the development of relief in East Africa.

As noted above, intrusive volcanicity has no immediate effect on the relief as the landforms occur underground. However, once the landforms have been exposed to the earth's surface by denudation, the relief will be affected. This is seen in the following ways:-Dykes when exposed to the earth's surface by denudation will affect the relief in three main ways:-

1. When the rocks making up the dyke are more resistant to erosion than the surrounding rocks, ridges or escarpments are formed. The surrounding rocks are worn down much faster leaving the dyke standing up as a wall-like feature or uplands e.g. Isingiro ridges on the boarder between Ankole and Masaka, Kyaka in Toro, the Mubende, Nakasongola and Singo batholiths in Uganda, Maragoli hills in Kenya and Tanganyika batholith between Mwanza and Iringa in Tanzania.

2. When the dyke rocks are of same resistance to erosion with the surrounding rocks, flatlands are formed, as the rocks will be worn down uniformly.

3. When the dyke rocks are of less resistance to erosion than the surrounding rocks, they are worn away much faster to form depressions e.g. the linear trenches or depressions west of Lake Turkana in Kenya.

4. In north central and north eastern Uganda, exposed basement granite rocks which are resistant to erosion stand-up as conical hills called inselbergs surrounded by plains e.g. at Labwor in Kotido, Kalongo in Pader and Parabong in Kitgum. Inselbergs are composed of hard or resistant rock that remains in place after surrounding material has eroded away.

Tors consist of piles of large rounded boulders and can be found on top of inselbergs. Granite tors include those in Mubende, Kachumbala, Nakasogola, Seme (near Kisumu) Lukenya hill (near Athi River) and the Bismarck rock at Mwanza. Their exposure largely depends on the rate of weathering.

Bornhardts are dome shaped outcrops larger than an inselbergs. They are gradually worn down by weathering to form castle kopjes. Castle kopjes include Koma rock near Nairobi, Chumvi hill near Machakos, Ngeta rock near Lira and Kalongo near Kitgum.

Sills if resistant to erosion form flat-topped hills as shown in Fig 6.003 and when crossed by rivers, waterfalls and rapids are formed e.g. the Sezibwa falls in Mukono and the Sipi falls in Kapchorwa. Sills are also common in the Thika District of Kenya.

The laccoliths form conical shaped hills when exposed to the surface by denudation e.g. at Voi in Kenya. The lopolith are very large saucer-shaped intrusions. The shape is as a result of increased weight causing sinking. After denudation the upturned edges may form out-facing scarps e.g. the giant lopolith semi-circular in shape extending from the Banana Island to Free Town in Sierra Leone while the saucer-shaped basin forms depressions.

Batholiths with lots of joints accelerate the rate of rock rotting by chemical weathering processes. The rocks therefore become weaker than the surrounding rocks and thus faster worn down to form depressions called arenas e.g. the Rubanda arena along Kabale-Kisoro road.

EXTRUSIVE VOLCANIC LANDFORMS AND FEATURES

Extrusive volcanic landforms and features are formed when material escape through a vent, crack or fissure onto the earth surface. The resultant landforms largely depend on the nature of materials ejected as noted earlier on in this chapter. The volcanic landforms and features formed by the extrusion of magma onto the earth's surface are discussed below:

Volcanic cones.

These are conical or dome-shaped structures built by the emission of lava and its contained gases from a vent or fissure in the earth's crust. The magma rises in a narrow, pipe like conduit from a magma reservoir far below the earth's surface. This material accumulates around the vent and repeated eruptions and accumulations lead to the building up of volcanic cones. The size and shape of a volcano depends mainly on the nature of materials erupted and the mode of eruption. Volcanoes therefore vary in size from small cones of only a few meters in height to vast mountains.

Types of volcanic cones

Composite cones or strato volcanoes

These are large volcanic cones with fairly steep upper slopes and gentle lower slopes. The gentler slopes near the base are due to accumulations of material eroded from the volcano and to the accumulation of pyroclastic material. The cones are composed of explosively erupted pyroclastic materials layered with non-explosively erupted lava flows and deposits of volcanic debris. The cones therefore consist of alternating layers of ash (explosively erupted pyroclastic materials) and lava (non-explosively erupted lava). The cones form large symmetric cones, with concave flanks, which get steeper toward summit. The lava flows cover the pyroclastic or ash layers preventing their erosion.

Illustration

Composite cones or strato volcanoes are formed through the accumulation of alternate layers of ash and lava around the vent over a long period of time. This type of volcano begins each eruption with a great violence and explosions due to the high content of gas in the magma. The material is blown to great heights where it breaks up into small fragments of ash falling around the vent. This accounts for the layers of ash. As the eruption gets underway, the violence ceases and the lava pours out forming lava layers on top of the ash. Repeated processes over a long period of time lead to the building up of volcanoes with alternating layers of ash and lava, which are usually large, and with fairly steep slopes.

After the eruptions, the magma solidifies in the central vent blocking the outlet. Secondary eruptions therefore occur through subsidiary vents to form parasitic cones on the sides of the main cone. Furthermore, a later explosion can blow off the top part of the volcanic cone to form a funnel shaped depression known as a crater or caldera depending on its size. In East Africa, Mts. such as Kenya and Longonot in Kenya, Kilimanjaro, Meru and Ol Doinyo Lengai in Tanzania, and Mount Elgon, Mount Mgahinga and Mount Muhavura in Uganda offer the best examples.

Mt Kilimanjaro is located in north-eastern Tanzania near the border with Kenya is the highest peak in Africa at a height of 5,858 meters above sea level. On this mountain, hree distinct inactive volcanoes can be seen. Kibo (center volcano) with the highest peak and a permanent glacier and snow field at its summit; Shira (most westerly), the oldest that has been eroded into a plateau-like feature standing at 3,778 meters above sea level; and Mawezi (most easterly) with a well-defined peak that reaches 5,354 meters above sea level. Although Kilimanjaro lies 3° south of the equator, the upper slopes are covered with glaciers due to its great height.

Mt Kenya is the second highest volcanic mountain in Africa, after Kilimanjaro. It rises to an elevation of 5,199 meters above sea level. Mount Kenya was created by massive, successive eruptions of a volcano 2.5 million to 3 million years ago. The mountain originally had a summit crater, but erosion wore the cone away.

The upper slopes of the mountain are snow and glacier-covered peaks, and valleys contain frozen lakes. However, over the years, the volcano's glaciers have been retreating rapidly due to warmer climate (global warming).

Mt. Meru is the second highest volcanic mountain in Tanzania after Kilimanjaro. It is located in north eastern Tanzania about 68 km west of Kilimanjaro. It stands at an altitude of 4,565 meters above sea level. It is an active volcano that last erupted in 1910.

Ol Doinyo Lengai in northern Tanzania is only 9,825 feet above sea level. It is an active volcano which last erupted in 2007.

Ash and cinder cones.

These are usually concave shaped volcanoes with fairly steep slopes. They frequently occur in groups. Their height does not usually exceed 300 meters in height. Ash and cinder cones These are usually concave are formed when lava is violently ejected due to the high gas content and blown to great heights where it breaks up into fragments of various sizes. The ash is smaller in size than the cinder. These fragments fall and accumulate around the vent to form ash cones. The lava is mainly acidic which is viscous hence forming volcanoes with steep slopes. Examples include Chuyulu hills of Machakos, Teleki, Murniau, Nabuyatom and Likaiyu hills south of Lake Turkana in Kenya and Sarabwe and Fileko in Tanzania. In Uganda, several ash and cinder cones exist in Kigezi especially along Kabale-Kisoro road between Kabale town and Muko, and between Muko and Ikamiro.

Basic lava cones or shield volcanoes

Basic lava cones or shield volcanoes are also referred to as basalt domes. Shield volcanoes derive their name from their distinctive, gently sloping convex slopes that resemble the fighting shields that many ancient warriors carried into battle. They are formed from basic lava, which is very fluid and mobile therefore, able to flow over long distances before solidifying. The volcanoes are constructed from several fluid basaltic lava flows that erupt non-explosively. Such flows can easily spread great distances from the feeding volcanic vents. Magma forming such volcanoes thus comes out through several vents instead of a single one. Consequently, the volcanoes formed are very low in height with gentle long slopes but with a very wide base.. Examples include Mounts Marsabit in northern Kenya, Tukuyu in southern Tanzania and Nyamulagira in the Uganda-DRC border.

Acid lava cones or cumulo domes

Acid lava cones or cumulo domes are volcanoes with steep convex slopes. They are formed from acid lava, which is viscous and cools quickly on reaching the earth's surface. Once the lava is ejected from the earth's crust, on reaching the earth's surface it cools and solidifies quickly around the vent forming a hard ring of higher ground, while the interior remains fluid.

Subsequent uprising of lava below the hardened layers forces them to expand outwards (just as air forces out shells of a football being inflated). As pressure from within continues, internal expansion takes place as layers are forced outwards within the acid cone and the shape becomes more rounded The volcanoes have no visible craters e.g. Mount Ntumbi east of Mbeya in Tanzania. Cumulo domes which form inside craters or calderas are called tholoids e.g. the one on Mount Rungwe south of Mbeya in Tanzania.

Explosion craters

Explosion craters are hollows found on top of low volcanic mountains occupying former volcanic fissures. The hollows formed are usually less than 500 meters in diameter and less than 50 meters in depth. Most explosion craters have a funnel shape. The bottom of the funnel opens into the channel or pipe through which the erupted material finds its way to the surface. Craters are formed when lava consisting of a lot of gaseous materials is violently ejected by blowing through the country rocks. The fragments derived are deposited around the depression forming a raised rim. Since the depressions extend towards the water table, they may be filled with water to form lakes. For example in the Lake George-Edward region there are over 200 explosion craters of which Lake Katwe crater is the largest. It has a diameter of 3 km surrounded by a high rim of about 90 meters. Others in the region include L. Nyungu, L. Kyamwiga, L. Nyamunuka, Mirambi, Kyamiga, Kyangambi and Itunga. Other examples include the crater on Mt. Marsabit in northern Kenya, Simbi crater near Kendu Bay and Lake Basotu crater north east of Singida in Tanzania.

Calderas

Calderas are large craters or rounded hollows on top of volcanic cones usually extending between one to fifty kilometer in diameter. Calderas can be formed in two main ways. Most calderas are formed due to cauldron subsidence or basal wreck. Originally there is a large reservoir of molten magma and gases under the volcano. An eruption ejects all the magma and gasses from a volcano leaving deep hollow (chasm) within the volcano. This is followed by the summit of a volcano collapsing into the chasm below due to the great weight of rocks overlying the chasm. This results in the formation of a depression known as a caldera, Calderas are often enclosed depressions that collect rain water and snow melt, and thus lakes often form within a caldera.

Other calderas are formed when violent gaseous explosions blow off the whole top of the volcano leaving a hollow as shown above. The Ngorongoro caldera in Tanzania offers the best example. The floor is much as 16 km wide in some places and cliff-like sides of over 600 meters high enclose it. Other examples of calderas include Lake Ngozi caldera in Tanzania, on Mts. Napak and Kadam in north eastern Uganda and Mts. Longonot, Menengai and Suswa in Kenya.

Illustration

Lava plains or lava plateau

Lava plateaus or basalt sheets are uplands of more or less flat relief made up of different layers of lava. They are formed from basic lava, which is fluid and mobile. The lava oozes or flows out from several fissures in the earth's crust and spread out over the surrounding countryside before solidifying. Hills and valleys may be buried by this lava. Successive lava flows result in the growth of a lava platform, which may be high and extensive enough to be called a plateau.

In Kenya the Yatta plateau east of Nairobi is a natural wall of lava 6-15 meters high, 3-5 km wide and the lava spreads out over a distance of 290 km. The lower Uasin Gishu plateau extends 140 km towards Mt. Elgon in Kenya. Other lava plateaus include Kapiti, Laikipia, Kericho and Simbara in Kenya and the Kisoro lava plains in south western Uganda.

Illustration

Volcanic plug or neck

A volcanic plug or neck is a high steep hill of bare volcanic rocks that stands out prominently above the surrounding landscape. It is formed from acid lava which is very thick and sticky. It is formed when a large mass of cylindrical lava solidifies in the vent of a cone and at the earth's surface. Being thick and sticky, it does not spread out from the cone. Generally, the longer a rock takes to solidify the harder it becomes. Thus, rock in the pipe or vent cool more slowly having been sheltered by the cone built around it, become harder than the layers of lava, which form the outer cone. Erosion removes the rest of the volcano leaving a distinct volcanic plug standing up for example the Tororo rock in eastern Uganda, Alekilek on Mount Napak, the Batian and Nelion peaks on Mt. Kenya and Mawezi on Mt. Kilimanjaro.

Illustration

Lava dammed lakes

These are lakes formed due to volcanicity in former river valleys. They are formed when multiple-lava flows from a volcanic cone and solidifies in a river valley thus blocking the flow of the river. Water collects behind the lava in the valleys to form lava dammed lakes. There is no explosive activity involved. Basic lava, which is fluid and mobile flows quietly through a vent and blocks a river valley. Examples include Lakes Bunyonyi in Kabale, Mutanda, Kayumba, Chahafi and Murche in Kisoro in south-western Uganda, as well as Lakes Kivu, Ruhondo and Bulera in Rwanda.

Illustration

Hot springs or thermal springs

A hot spring is a steam of hot water flowing from the under ground rocks to the earth's surface continuously. It is formed when rain water sinks far enough into the earth and gets in contact with rocks heated by contact with hot magma rocks. When the crack above these rocks is large enough, convectional currents will take place resulting into a continuous flow of hot water at the surface as a hot spring. Hot springs therefore commonly occur in volcanic regions where eruptions have ceased. Examples include Sempaya near Fort-Portal, Kitagata in Sheema, Kisiizi in Rukungiri, Kibiro east of Lake Albert. In Kenya hot springs occur in the rift valley region e.g. Maji ya moto near Nakuru, Homa south of Nyanza and around Eldorate, Lake Hannington and Maji Moto in northern Tanzania near Lake Manyara.IM

Illustration

Geysers

Geysers are similar to hot springs except they eject hot water and steam into the atmosphere at irregular intervals. From the mouth of the geyser is a tube or crack penetrating deep into the earth crust up to the hot magma rocks. The hot rocks super heat the water in the tube or crack in contact with them. However, the tube or crack is deep but too narrow to allow convectional currents to take place freely. The temperature of the water in contact with the hot rocks below thus continues to rise while that at the top of the tube is relatively cool. When the temperature of the water reaches 100°C and above it is ejected out and the activity ceases. More water will fill the crack and the process is repented. Examples include the geysers at the shores of Lake Hannington, at Longonot between Lakes Baringo and Nakuru and Bogoria geysers in Kenya.

Illustration

Solfatara

These are volcanoes, which only emit gases and steam. The gases are mainly sulphurous e.g. the solfataras at Eburru between Naivasha and Gilgil and Eldama Ravine in the Baringo district in Kenya.

Illustration

Fumerole

These are vents in the earth's crust from which steam and gases, such as sulphur dioxide and carbon dioxide, are emitted under low pressure into the atmosphere. They are frequently found in dormant volcanic regions. The steam is produced by the magma beneath the surface, when the volcano has ceased to erupt e.g. around Mount Kilimanjaro, in the Menengai caldera, Longonot and Eburu areas.

Illustration

ECONOMIC IMPORTANCE OF VOLCANIC FEATURES IN EAST AFRICA

1. Volcanic features create beautiful scenery attractive to tourists hence earning the respective East African countries foreign exchange. In particular, the snow capped volcanic mountains such as Kenya and Kilimanjaro for site seeing and mountain climbing, and other relief landforms such as such as Ngorongoro caldera, Tororo volcanic plug and several hot springs such as Ihimba along Kabale-Katuna road and Kitagata in Sheema in western Uganda.

2. Volcanic rocks have weathered to produce fertile soils important for agriculture. The districts of Bubulo, Bududa, Manafwa and Sironko on the slopes of Mount Elgon produce large quantities of Arabica coffee, bananas and vegetables. The districts of Bukwo and Kapchorwa on Mount Elgon produce large quantities of maize and wheat. The Kigezi Highlands in south-western Uganda are undoubtedly the most densely populated and intensively cultivated region in Uganda due to the fertile volcanic soils. Coffee and various vegetables are grown. Other areas with fertile volcanic soils, which are intensively cultivated, include the Kenya Highlands and the slopes of Mountain Kilimanjaro.

3. Volcanic rocks contain valuable minerals, which are of great economic importance to the East African countries. These include limestone and phosphates in the Sukulu and Bukusu hills around Tororo used to manufacture cement and artificial fertilizers respectively, tin and wolfram in Kigezi and phosphates near at Minjungu near Lake Manyara in Tanzania. The diamonds mined at Mwadui near Shinyanga in Tanzania are derived from volcanic intrusions made up of ultra-basic rocks called Kimberlite. The minerals provide employment and revenue to the respective countries. At Lake Magadi, soda ash is mined and processed at the Magadi Soda factory for a wide range of industrial uses.

4. Igneous out crop rocks are quarried to provide concrete and gravel used in the construction and building industry e.g. the volcanic rocks forming hills which are quarried near Kabale town, on the slopes of Mt. Elgon and the granite rocks at Nyero in Kumi and Nalugombe in Wakiso. Building stone is processed from the volcanic lava common to most of Kenya.

5. Explosion craters such as that containing Lake Katwe and Lake Magadi provide salt that is used for human and animal (cattle) consumption as well as for export. It is also used in the chemical industry for the preparation of caustic soda, soap and chlorine.

6. Volcanic mountains such as Kenya, Elgon and Kilimanjaro modify the climate of the surrounding areas. When warm moist wind meets such high ground, it is forced to ascend it, thereby cooling and condensing resulting into the formation of heavy orographic rainfall. Most volcanic mountain areas in East Africa receive heavier rainfall than the surrounding areas hence intensively cultivated e.g. the south slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, south west slopes of Mount Kenya and the western slopes of Mount Elgon hence promoting agriculture.

7. Volcanic mountains are sources of many rivers rising from the heavy rainfall and the melt waters from glaciers. These rivers are being used for various purposed e.g. Tana River flowing from Mt. Kenya is used to generate hydro-electric power at Seven Forks power scheme while the Pangani River from Mt. Kilimanjaro is used in the generation of HEP at the Pangani Power Project. Other uses of rivers include irrigation e.g. River Manafwa used to irrigate the Doho Rice Scheme in Butaleja and source of water for Mbale town while River Malaba is a source of water for Tororo town.

8. Hot springs and geysers are not only important tourist attractions but also have many other uses. The waters contain minerals such as sulphur, iodine, lithium and calcium of medicinal value. The local people around hot springs such as Thimba along Kabale-Katuna road, Sempaya in Bundibugyo, Kitagata in Sheema, Amoropii in Nebbi, and geysers around Lake Bogoria, are used for the treatment of ailments such as headaches, backaches, as well as eye and skindiseases.

9. Local residents around Chamka near Lake Elmentaita in Kenya depend on the hot springs around for domestic water freshwater supply, subsistence irrigation, and water for livestock, while the nomadic Maasai use the calcium in brought by the hot springs for salt-licking for their cattle. At Lake Bogoria Hotel, hot water from hot springs is directed towards a swimming pool, in which hotel guests like to bathe.

10. Volcanic mountains are covered with various vegetation types especially on the windward slopes which are of great economic importance. Mount Kenya and Mount Kilimanjaro have various tree species such as Mvule, green heart and ebony which are used as a source of timber.

11. Conservation of wildlife is carried out in gazette areas located on volcanic mountains. Mount Elgon Forest National Park, Mount Kilimanjaro National Park, Mount Meru National Park are homes to various animals such as forest hogs, monkeys and baboons, as well as vegetation species such as the groundsel and lobelia which promote the tourism and revenue generation.

12. Lava dammed lakes such as Bunyonyi, Mutanda and Murehe are important tourist attractions, sources of fish as well as a means of cheap water transport.

Challenges caused by the volcanic features in East Africa.

In volcanic highlands, roads have to wind over long distances avoiding areas of steep gradients. This makes the development of transport and communication routes difficult and expensive e.g. in Kigezi, Bundibugyo, Kapchorwa and Southern Highlands of Tanzania.

The steep slopes in volcanic highlands promote soil erosion e.g. on the cultivated slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro, Mt. Elgon and the Kigezi highlands. Soil erosion reduces the productivity of the land for agriculture.

Volcanic mountains act as climatic barriers on the leeward slopes. Regions on the leeward side of the mountain range receive low rainfall which hinders landuses such as settlement and farming e.g. the northern slopes of Mount Kenya and Kilimanjaro, and the eastern slopes of Mount Elgon.

The volcanic highlands and mountain regions are susceptible to landslides. The combination of heavy rainfall and steep slopes twig off down hill movement of large quantities of earth under the influence of gravity. Landslides have occurred in Bundibugyo, Manjiya and Bulucheke on the slopes on Mount Elgon, Aberdare ranges, as well as Muranga, Nyeri and Kirinyanga on the slopes of Mount Kenya. The most recent landslide in Uganda occurred in Bulambuli in 2010. Landslides lead to loss of lives, displacement of people, destruction of; transport, communication lines and agricultural.

Active volcanic mountains lead to loss of life of both man, animals and property due to falling ash and lava flows during eruptions e.g. at Nyamulangira and Nyirangongo volcanoes on the Rwanda and DR Congo boarders.

Young volcanic soils tend to be in infertile, as they have not been exposed for long to gents of weathering. This is made worse by the continuous deposition of layers of lava in the plains. The soils are also porous and easily eroded once formed e.g. in Kisoro.

Very cold temperatures are experienced on the upper slopes of volcanic mountains such as Mounts Kenya, Elgon and Kilimanjaro due to high altitude and this discourages settlement and other forms of land use.

Some volcanic regions lack surface water e.g. Kisoro in south western Uganda. This is because the volcanic rocks are pervious and allow water to seep through, making it difficult to find surface water near the earth surface.

Volcanic highlands with steep slopes necessitate the building of terraces if they are to beused for cultivation e.g. in the Kigezi Highlands. The presence of steep slopes further limits mechanisation.

FAQs

1. What is vulcanicity in geography?

Vulcanicity refers to all the processes and phenomena associated with the movement of molten rock (magma) from beneath the Earth's crust to its surface.

2. What are the main causes of vulcanicity in East Africa?

Vulcanicity in East Africa is primarily caused by tectonic plate movements and the development of the East African Rift Valley.

3. Which are the major volcanic mountains in East Africa?

Notable volcanic mountains include Mount Kilimanjaro, Mount Kenya, and Mount Elgon.

4. What are the positive impacts of vulcanicity in East Africa?

Benefits include fertile soils for agriculture, geothermal energy sources, and tourism from unique landscapes and volcanic features.

5. Are there any active volcanoes in East Africa?

Yes, Ol Doinyo Lengai in Tanzania is one of the few active volcanoes in East Africa.

6. How does vulcanicity affect the environment in East Africa?

Vulcanicity can cause both positive effects (such as nutrient-rich soils) and negative impacts (like destruction from eruptions and lava flows).

7. Why is the Rift Valley important to vulcanicity in East Africa?

The Rift Valley is a major tectonic feature that facilitates magma movement, making it a hotspot for volcanic activity.

8. What are the main types of vulcanicity?

Vulcanicity is categorized into intrusive (magma solidifies below the surface) and extrusive (lava erupts onto the surface).

9. How are volcanic landforms in East Africa formed?

Landforms like volcanic mountains, craters, and lava plateaus are formed through the cooling and solidification of magma or lava.

10. What is the significance of geothermal energy from volcanic regions in East Africa?

Geothermal energy from volcanic areas, like the Olkaria plant in Kenya, provides a renewable and eco-friendly energy source.

11. What are some famous crater lakes in East Africa?

Notable examples include Lake Chala (near Mount Kilimanjaro) and Lake Bunyonyi in Uganda.

12. What hazards are associated with vulcanicity in East Africa?

Hazards include lava flows, ash clouds, volcanic gas emissions, and potential displacement of communities.

13. How does vulcanicity contribute to tourism in East Africa?

Features like Mount Kilimanjaro, geysers, and hot springs attract thousands of tourists annually, boosting the local economy.

14. Can vulcanicity affect climate patterns in East Africa?

Large volcanic eruptions can release ash and gases into the atmosphere, temporarily affecting regional and global climate patterns.

15. What are some examples of historical volcanic eruptions in East Africa?

The 2007 eruption of Ol Doinyo Lengai is a notable recent example, characterized by its unique carbonatite lava.

Conclusion

Vulcanicity in East Africa is a remarkable natural phenomenon shaped by the region's unique geological features, particularly the East African Rift Valley. It has given rise to awe-inspiring landscapes, including volcanic mountains, craters, and hot springs, which not only enrich the environment but also provide valuable resources such as fertile soils and geothermal energy. However, alongside its benefits, vulcanicity also presents challenges, such as volcanic hazards and environmental disruptions.

Understanding vulcanicity helps us appreciate its role in shaping East Africa's geography, culture, and economy. By balancing exploration, conservation, and mitigation strategies, we can harness its benefits while minimizing risks. Vulcanicity remains a testament to the Earth's dynamic processes, making East Africa a region of both scientific intrigue and natural beauty.