The Science of Memory Why Do We Forget Things

Forgetting is a normal and helpful function of the brain that involves removing unneeded information to free up space for new memories and improve how we process new data. Known as decay theory, this process allows the brain to focus on storing the most important information for the long term. Although memories may fade naturally over time, forgetting can also be affected by factors such as neurogenesis (the formation of new neurons) and the brain’s capacity to adjust memory recall based on changes in the environment.

The science of memory is a multifaceted field that explores how we encode, store, and retrieve information, as well as the reasons behind forgetting. Memory is crit- ical for daily functioning and learning, and its study encompasses various types, including sensory, short-term, and long-term memory, each serving distinct purposes and processes.[1][2][3] Understanding memory is essential not only for cognitive psychology but also for applications in education, mental health, and aging, making it a topic of significant interest and research.

Forgetting, while often perceived as a negative phenomenon, plays a crucial role in memory management and cognitive efficiency. Several theories have been proposed to explain why we forget, including trace decay theory, interference theory, and moti- vated forgetting. These theories highlight the complexities of memory processes and illustrate how our brains prioritize certain information while discarding the irrelevant or unhelpful.[4][5] Notably, motivated forgetting can serve as a defense mechanism against emotional distress, revealing the intricate relationship between memory and psychological well-being.[6][7]

The biological underpinnings of memory involve intricate neural mechanisms, par- ticularly the roles of key brain structures such as the hippocampus and amygdala. These structures facilitate memory formation and retrieval, emphasizing that memory is not a singular entity but rather a collaborative process involving various regions of the brain.[8][9] Factors such as age, stress, and environmental conditions also

Overall, the science of memory is a dynamic and evolving field that continues to unravel the complexities of how we remember, forget, and manage our mental lives. Its implications extend into numerous domains, from enhancing educational practices to informing therapeutic strategies for mental health, underscoring the significance of understanding memory in our everyday lives.

Types of Memory

Memory can be classified into several distinct types, each serving specific functions and characteristics, often overlapping in everyday life. The major categories of mem- ory include sensory memory, short-term memory, working memory, and long-term memory, with further subdivisions in the latter category.

The Process of Memory Formation

Memory formation is a complex and dynamic process that involves several stages: encoding, storage, and retrieval. Each of these stages plays a crucial role in how we perceive, maintain, and access information.

Encoding: The First Step

Encoding is the initial phase of memory formation, where sensory input is trans- formed into a format that the brain can interpret and store. This process begins when our sensory systems relay information to the brain, converting stimuli—such as sights, sounds, and smells—into neural signals. The hippocampus is primarily re- sponsible for forming explicit memories during this stage, highlighting its importance in the encoding process[13][14].

Different types of encoding exist, including visual, acoustic, and semantic encoding. Research indicates that semantic encoding, which involves attaching meaning to information, is particularly effective for long-term retention[15][16]. For example, using acronyms or creating associations can aid in memorizing complex information, as these methods help encode details more meaningfully.

Storage: Keeping Information Over Time

Once information is encoded, it enters the storage phase, where it is maintained for future use. Memory storage occurs across various regions of the brain, depending on the type of memory being formed. Short-term memory, or working memory, holds information temporarily, typically for about 20 to 30 seconds, and is associated with the prefrontal cortex[17]. In contrast, long-term memory, which can store information indefinitely, is primarily linked to the hippocampus and amygdala.

Long-term memory is further categorized into explicit (declarative) and implicit (non-declarative) memory. Explicit memory involves conscious recollection of facts

Retrieval: Accessing Stored Information

Retrieval is the final stage in memory formation, where stored information is accessed for use. This process can be influenced by various factors, including cues that may trigger the recall of specific memories. For instance, providing contextual cues or categories can significantly enhance the ability to retrieve information that may otherwise feel forgotten[15]. The interplay of attention, emotional connection, and the context in which information was encoded also plays a role in how effectively memories are retrieved[1][18].

Theories of Forgetting

Forgetting is a complex psychological phenomenon, and numerous theories have been proposed to explain why we forget information. These theories encompass various aspects of memory processes and provide insights into the mechanisms behind forgetting.

Trace Decay Theory

The trace decay theory of forgetting, formulated by Edward Thorndike in 1914, suggests that memory fades over time if not accessed regularly. This theory is rooted in early studies by Hermann Ebbinghaus, who observed that memory retention decreases as time passes.[4] According to this theory, neurochemical changes occur in the brain when new information is learned, creating memory traces. Successful retrieval of memories depends significantly on the time elapsed between encoding and recall; quicker retrieval typically leads to more effective recall.[4]

Displacement Theory

The displacement theory of forgetting, theorized by George Muller and Alfons Pilzeck- er in 1900, is primarily applicable to short-term memory. This theory highlights the limited capacity of short-term memory, which can retain about seven items at a time. When new information is introduced, older items may be displaced and forgotten as a result.[4]

Interference Theory

Interference theory posits that forgetting occurs due to interference from previously learned information or new information. It can manifest as proactive interference, where older memories hinder the recall of newer information, or retroactive inter- ference, where new information disrupts the retrieval of older memories.[19] This theory is supported by the principle of response competition, which indicates that multiple memories may compete for retrieval, increasing the likelihood of incorrect recall.[19] Output interference, where the retrieval of competing items affects memory performance, has also been demonstrated in psychological studies.[19]

Retrieval Failure Theory

Developed by Endel Tulving in 1974, the retrieval failure theory suggests that for- getting occurs when individuals cannot access stored information, even though it remains intact in long-term memory. This often manifests in situations where a word or concept feels "stuck" at the tip of the tongue. The theory identifies two primary causes for retrieval failure: ineffective encoding, where the information never reaches long-term memory, and a lack of effective retrieval cues during the recall attempt.[4]

Consolidation Theory

Consolidation is the process by which newly acquired memories are stabilized into long-term storage. Failures in this process can lead to forgetting, particularly in sit- uations where distractions occur during the learning phase. Research indicates that consolidation can take time and may not be completed immediately after encoding, affecting memory strength over the long term.[19]

Motivated Forgetting

Another perspective on forgetting is the concept of motivated forgetting, which involves the suppression of memories that are deemed psychologically painful or unacceptable. Sigmund Freud's theory of repression exemplifies this, suggesting that individuals may unconsciously push unwanted thoughts out of their conscious awareness to avoid psychological discomfort.[5]

Adaptive Forgetting

Adaptive forgetting refers to the brain's natural tendency to eliminate information that is no longer relevant or useful, effectively streamlining memory storage for more pertinent information. This process can be likened to decluttering one’s mental space, discarding memories that do not serve a current purpose.[5]

Understanding these theories provides valuable insights into the nature of memory and forgetting, highlighting the complexities of how our minds process and manage information over time.

Biological Basis of Memory

Memory is intricately linked to various biological processes that occur within the brain. Understanding how memory works requires a closer examination of the neural mechanisms involved in encoding, storing, and retrieving information.

Memory Formation

Encoding

The first step in the memory process is encoding, where sensory input from the environment is transformed into a format that can be stored in the brain. Sensory memories are initially fleeting, lasting only a few seconds, but when attention is directed to a particular stimulus, this information is transferred from sensory memory to short-term memory. Attention acts as a filter, determining which information is deemed significant enough for further processing[18][2].

Types of Memory

Different types of memory exist, each serving unique functions. These include episodic memory, semantic memory, procedural memory, working memory, and sensory memory. Each type is processed and stored in distinct brain regions, often involving key structures such as the hippocampus and cerebral cortex. For instance, episodic memories, which involve personal experiences, depend heavily on the hippocampus for formation and retrieval[8][2].

Neuroanatomy of Memory

Key Brain Structures

The hippocampus is critical for the formation of long-term memories and is intercon- nected with various parts of the brain. It works in conjunction with the amygdala, which is involved in processing emotions related to memories, thus highlighting the emotional context of certain experiences[9][20]. Additionally, the cerebellum plays

Distribution of Memory

Memories are not localized to a single area; instead, the components of a memo- ry—such as its sensory details—are distributed across various brain regions. The act of recalling a memory involves the brain reconstructing these pieces, demonstrating the collaborative nature of memory storage and retrieval[9][2].

Factors Influencing Memory

Age and sleep significantly influence memory performance. Aging can lead to a decline in certain memory functions, but other aspects, such as semantic memory, may improve. Furthermore, adequate sleep is essential for memory consolidation, as it stabilizes and integrates newly acquired information[10][2]. Hence, maintaining good sleep hygiene and understanding the biological mechanisms of memory can help enhance memory retention and recall throughout one's life.

Psychological Aspects of Forgetting

Motivated forgetting is a complex psychological phenomenon wherein individuals suppress or avoid certain memories, often as a defense mechanism against emo- tional distress or to maintain their psychological well-being. At its core, motivated forgetting acts as a coping strategy, allowing the mind to manage experiences that may be too painful or embarrassing to confront directly[5][6]. This is distinct from simple forgetfulness; rather, it is a deliberate or subconscious process aimed at regulating one's emotional state and self-image.

Types of Motivated Forgetting

Motivated forgetting manifests in various forms, each characterized by different mechanisms:

Intentional Forgetting

Intentional forgetting involves a conscious effort to forget particular memories. For example, individuals may try to erase memories of a painful breakup or a humiliating incident[5]. This active suppression can be likened to attempting to wipe a slate clean, although residual feelings or thoughts may linger.

Directed Forgetting

Directed forgetting is often studied in experimental settings where participants are instructed to forget certain pieces of information. This approach resembles a game of "Simon Says," where compliance leads to selective memory erasure[5]. Research in this area has provided insights into how directives can influence memory retention.

Think/No-Think Paradigm

In the think/no-think paradigm, participants are cued to suppress thoughts of specific memories. This scenario serves as a mental exercise in controlling what to remember and what to forget, providing valuable data on cognitive control over memory[5].

Adaptive Forgetting

Adaptive forgetting refers to the brain's natural tendency to discard information that is no longer useful. This process allows individuals to streamline their cognitive resources and focus on more relevant experiences, akin to decluttering one’s mental space[5].

Theories Behind Motivated Forgetting

Several theories aim to explain why motivated forgetting occurs. Sigmund Freud's theory of repression posits that individuals unconsciously push distressing memories into the unconscious mind to avoid psychological pain[7]. This notion suggests a

Another angle considers the psychological factors at play, suggesting that traumatic experiences trigger motivated forgetting as a means of self-preservation. Individuals may suppress memories related to trauma to mitigate emotional suffering, demon- strating the intricate link between memory and mental health[6].

Implications of Motivated Forgetting

Understanding motivated forgetting holds potential for therapeutic applications, es- pecially in treating trauma. Therapists may harness the mechanisms of motivated forgetting to help clients process painful memories, ultimately leading to improved mental health outcomes. The ability to facilitate forgetting harmful thought patterns or traumatic experiences could transform therapeutic practices, offering new avenues for healing[5][7].

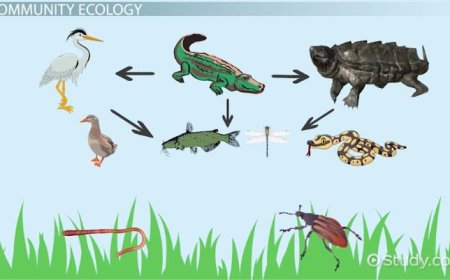

Environmental Factors Influencing Memory and Forgetting

Memory and forgetting are influenced by a variety of environmental factors, ranging from air quality to social interactions. These elements can significantly impact cogni- tive function and the ability to retain and recall information.

Lifestyle Factors

Certain lifestyle choices significantly contribute to memory function. Regular physical exercise has been proven to promote the formation of new neural connections and enhance cognitive abilities. Activities such as walking, yoga, and other forms of movement not only improve physical health but also bolster memory retention and recall capabilities.[6][11][9] Moreover, maintaining a balanced diet rich in nutrients, particularly those beneficial for brain health, is crucial. Diets such as the Mediter- ranean diet have been associated with lower risks of cognitive impairment and improved memory outcomes.[9]

Air Quality and Cognitive Function

Research indicates that environmental pollution, particularly air quality, can affect memory and increase the risk of cognitive decline. Studies have shown a correlation between exposure to poor air quality and a higher likelihood of developing Alzheimer’s disease.[6][11] Furthermore, individuals exposed to pollutants during childhood may experience long-term cognitive effects, highlighting the importance of maintaining clean air for optimal brain health.

Stress and Memory Disturbance

High levels of stress are known to negatively influence memory processes. Chronic stress has been linked to various cognitive impairments and is especially pronounced in conditions like PTSD, where individuals may experience significant memory dis- turbances.[6][11] Additionally, the psychological burden of stress can interfere with daily functioning and the ability to recall important information.

Social Interaction and Cognitive Health

Engaging in quality social interactions has been shown to benefit memory and overall cognitive health. Social bonds and community connections can protect against cognitive decline, as regular interaction with others stimulates mental activity and emotional well-being.[11][9] Participation in support groups or community activities can enhance memory retention and improve mental resilience.

The Role of Environment in Cognitive Function

The broader environment, including socio-economic factors, safety perceptions, and community composition, also plays a role in cognitive health. Factors such as socio-economic status and community education levels are positively correlated with cognitive function, while environmental stressors like pollution can detract from it.[12] Therefore, a secure, connected, and supportive environment can promote better cognitive health and memory retention, especially in older adults.

External Conditions Affecting Memory Retrieval

Memory retrieval is significantly influenced by various external conditions that create the context in which memories are stored and recalled. These conditions can en- hance or impede the ability to access memories, highlighting the intricate relationship between our environment and cognitive processes.

Contextual Cues

One of the primary external factors affecting memory retrieval is the presence of contextual cues. These cues can be environmental elements such as sounds, smells, or specific locations that were present during the original encoding of the memory. For instance, entering a bakery may trigger the recollection of pleasant experiences associated with similar aromas if they were encountered previously[24]. Research indicates that memories are more easily retrieved when the context at retrieval matches the context during encoding, suggesting that the surrounding environment plays a crucial role in memory recall[25].

Impact of Stress and Mood

Stress and mood also play significant roles in memory retrieval. Mild stress can enhance memory recall, as it heightens alertness and focus. However, chronic stress can be detrimental, negatively affecting both the encoding and retrieval processes[- 10]. Similarly, a person’s emotional state can influence their ability to remember even- ts; for example, individuals feeling sad may struggle to recall positive memories due to a mismatch between their current emotional context and that of the memory[26].

The Role of Medications

Medications can also impact memory retrieval by altering the brain's neurotransmitter systems. Certain drugs, particularly those prescribed for anxiety or insomnia, have been linked to memory impairments. For example, benzodiazepines can interfere with procedural memory, making it challenging to learn and perform tasks that require sequential actions[22][27]. Understanding how these medications affect memory can help healthcare providers tailor treatment plans and mitigate potential cognitive side effects.

References

[1] : Types of Memory: Short-Term, Long-Term, Working Memory, and More

[2] : Memory | Psychology Today

[3] : Types of Memory | Psychology Today South Africa

[4] : Types of Memory - Psychology Today

[5] : Types of memory - Queensland Brain Institute

[6] : How Memory Works: The Science Behind Brain and Recall

[7] : Understanding the Memory Process: Encoding, Storage, and Retrieval

[8] : Encoding (memory) - Wikipedia

[9] : Memory (Types + Models + Overview) - Practical Psychology

[10] : The Psychology of Memory: Exploring How We Remember and Forget

[11] : The Biology of Memory: How We Remember and Why We Forget

[12] : Theories of Forgetting - Unacademy

[13] : Theories of Forgetting: Explaining Memory Failure—Viquepedia

[14] : Motivated Forgetting: Psychology's Selective Memory Process

[15] : To Remember, the Brain Must Actively Forget | Quanta Magazine

[16] : Memory - Harvard Health

[17] : Working memory - Wikipedia

[18] : 8.2 Parts of the Brain Involved in Memory

[19] : Understanding Procedural Memory: A Key Component of Psychology [20]: Brain Memory: How We Store and Recall Information

[21] : The Science of Forgetting: Exploring Why We Forget in Psychology

[24] : How Does The Environment Impact Memory? - EcoMENA

[25] : Individual and environmental factors associated with cognitive function ...

[26] : What Are the Three Processes of Memory? A Comprehensive Overview.

[27] : Theories of Forgetting in Psychology

[28] : What Makes Memory Retrieval Work—and Not Work?

: Forgetfulness: What is "normal" memory loss? - Harvard Health