Could This Strange "Immortal" Worm Unlock the Secret to Reversing Aging?

A tiny flatworm with an extraordinary ability to regenerate may hold the key to reversing aging—not just in worms, but potentially in humans too.

Researchers at the University of Michigan Medical School are exploring how planarians, often referred to as "immortal worms," can seemingly defy aging. These flatworms (Schmidtea mediterranea) can regrow entire body parts, including new heads and eyes, even after being decapitated. Their regenerative powers have fascinated scientists for over a century, but the exact mechanisms that allow them to maintain youthfulness are only now beginning to be understood.

Understanding Aging and Regeneration

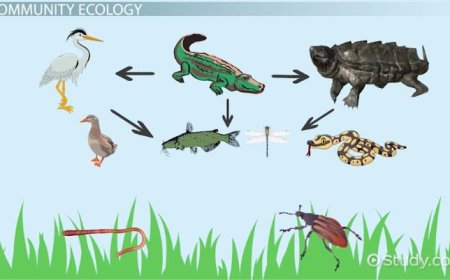

As living organisms age, they naturally experience a decline in physical functions—loss of neurons and muscle tissue, reduced fertility, and slower healing are just some of the common signs. While lifestyle changes like calorie restriction and exercise have shown promise in slowing aging or rejuvenating specific tissues in animals, reversing aging across an entire organism remains a major scientific challenge.

Dr. Longhua Guo, an assistant professor at the U-M Medical School and a member of the U-M Institute of Gerontology, has been using planarians as a model to study aging. Unlike most animals, these worms do not seem to experience a complete breakdown of function with age—and even when they do show signs of aging, regeneration appears to reset their biological clock.

Planarians Grow Younger with Regeneration

Guo and his research team focused on sexually reproducing planarians, tracking them from the earliest stages of development (zygote) up to around 18 months of age. Interestingly, even these worms—considered long-lived—show signs of aging, including a reduction in muscle mass, fertility, and neuron numbers. One of the clearest indicators of aging in planarians is the appearance of abnormalities in their eyes.

However, in a remarkable discovery, when the heads of older planarians were removed, the newly regenerated heads formed normal, youthful eyes. Not only did the worms regenerate healthy organs, but their overall reproductive ability and physiological health also improved after regeneration—suggesting a true reversal of aging at the organism level.

Unique Stem Cell Preservation

The researchers, whose findings were published in Nature Aging, noted a major difference between planarians and mammals: unlike humans and mice, planarians do not lose their adult stem cells as they age. These cells are essential for tissue repair and regeneration.

Guo explained, “Older planarians don’t just retain their regenerative ability—they can completely rebuild themselves, even at advanced ages. This indicates they have unique biological mechanisms that allow them to maintain longevity and health far beyond what’s typical in other animals.”

Furthermore, regeneration in planarians appeared to restore gene activity patterns across various tissues, effectively reversing the molecular signs of aging.

Aging Patterns Shared Across Species

To understand how planarian aging compares to other organisms, Guo’s team analyzed single-cell RNA sequencing data and compared it to datasets from aging mice, rats, and humans, as well as mice treated with known anti-aging interventions.

They discovered that the gene expression signatures of aging in planarians are strikingly similar to those found in aging mammals—and even more interestingly, to those seen in mice whose lifespans were extended through scientific interventions.

This suggests that the biological pathways that regulate aging may be conserved across species, opening up exciting possibilities for applying what’s learned from planarians to more complex animals, including humans.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Age Reversal

Guo’s next step is to identify the specific genes and cell types involved in the regeneration process that leads to age reversal in planarians. Understanding these could pave the way for breakthroughs in regenerative medicine and anti-aging therapies.

“The key message from our study,” Guo said, “is that age-related decline may not be inevitable. In some organisms, it’s reversible. And what we learn from them might one day help us extend healthspan and reverse aging in humans.”